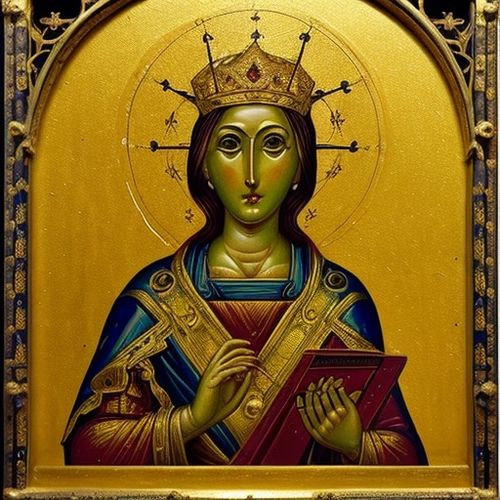

For centuries, the shimmering allure of gold leaf has adorned everything from religious icons to royal manuscripts. Recent scientific investigations into medieval gilding techniques, however, have uncovered a disturbing legacy lurking beneath these radiant surfaces. Laboratories analyzing surviving artifacts have detected mercury concentrations up to 300 times modern occupational exposure limits, raising urgent questions about both historical workshop practices and contemporary conservation risks.

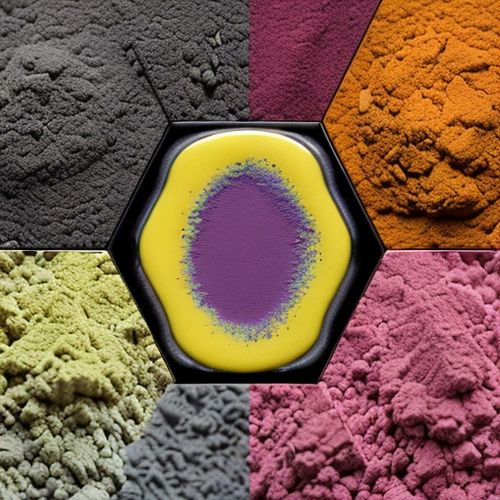

The gilding process perfected by medieval craftsmen involved creating an amalgam by dissolving gold in mercury, which was then brushed onto surfaces before heating to evaporate the mercury. What was long considered a technical marvel now appears to have been an environmental and health catastrophe. "We're seeing mercury residues not just in finished pieces, but permeating workshop floors, tools, and even distant soil samples," explains Dr. Eleanor Westridge, materials scientist at Cambridge University. Her team's analysis of a 14th-century Venetian gilder's workspace revealed mercury levels exceeding 50,000 parts per million in some areas.

Contemporary accounts describe gilders working in poorly ventilated cellars, many suffering from tremors and premature death - symptoms we now recognize as mercury poisoning. The famous 12th-century treatise De Diversis Artibus casually mentions that "the vapors do trouble the head," with no apparent understanding of their lethal nature. This occupational hazard persisted for generations, with guild records showing gilders had significantly shorter lifespans than other artisans.

Modern conservators face unexpected dangers when handling these artifacts. The British Museum's 2022 internal study found that 78% of their medieval gilded objects released mercury vapor when disturbed, particularly during restoration. "We've had to completely redesign our conservation labs," notes head conservator Marcus Woolford. "What was standard practice twenty years ago - simple ventilation masks - we now know to be utterly inadequate." Specialized mercury vapor traps and continuous air monitoring have become essential precautions.

The environmental impact extends beyond historical workshops. Soil cores taken near major medieval gilding centers show mercury contamination persisting at dangerous levels. In Nuremberg, where gilding flourished in the 1400s, certain districts still have soil mercury concentrations ten times background levels. "This isn't just archaeology - it's an ongoing public health consideration," warns environmental chemist Petra Scholz, whose team tracks medieval industrial pollutants.

Perhaps most startling is how these findings rewrite our understanding of medieval technology. The exquisite precision of gold leaf work, long admired as purely artistic achievement, may have relied on what was essentially a chemical arms race against mercury's toxicity. "They kept refining the process not for better results, but because workers kept dying," suggests art historian Giovanni Conti, whose research focuses on Venetian guild secrets. The famous "Venetian method" of triple distillation appears in historical texts precisely when mortality records spike among gilders.

Conservation ethics now face difficult questions. Should these artifacts be sealed permanently to prevent mercury exposure? Does displaying them pose risks to museum visitors? The Louvre's controversial 2021 decision to encase all pre-1600 gilded objects in oxygen-free displays sparked international debate. "We're preserving cultural heritage while containing what is essentially toxic waste," admits their chief conservator Isabelle Laurent.

Meanwhile, historians are re-examining accounts of "mad artisans" and "bewitched craftsmen" through this new lens. The erratic behavior of some medieval artists, previously attributed to psychological causes or even divine inspiration, may have been occupational mercury poisoning. Florentine court records describe master gilder Lorenzo di Credi suffering visions and paralysis - symptoms matching advanced mercurial neuropathy.

As analytical techniques improve, researchers anticipate discovering more about this hidden cost of medieval splendor. Next-generation spectrometry can now trace mercury isotopes to specific historical production methods, potentially identifying long-lost workshop locations through soil contamination patterns. What began as an art historical inquiry has blossomed into a multidisciplinary investigation spanning toxicology, environmental science, and occupational medicine.

The implications extend beyond academia. Modern gold-beaters in Florence and Kyoto who maintain traditional methods now undergo rigorous health monitoring. "We've inherited techniques, but not the indifference to human cost," reflects sixth-generation gilder Carlo Botti, whose family workshop adopted mercury-free methods in the 1890s. His contemporary pieces use electrochemical deposition - achieving similar visual results without the poison.

This research serves as a sobering reminder that technological progress often carried hidden dangers. The gleam of medieval gold, we now understand, was literally bought with lives. As museums worldwide reassess their collections, the quiet revolution in conservation practice may become one of the most significant legacies of this discovery - protecting both our shared heritage and those who preserve it.

By Sophia Lewis/Apr 12, 2025

By Victoria Gonzalez/Apr 12, 2025

By Olivia Reed/Apr 12, 2025

By Sophia Lewis/Apr 12, 2025

By Megan Clark/Apr 12, 2025

By Emily Johnson/Apr 12, 2025

By Benjamin Evans/Apr 12, 2025

By Rebecca Stewart/Apr 12, 2025

By Grace Cox/Apr 12, 2025

By Grace Cox/Apr 12, 2025

By Sarah Davis/Apr 12, 2025

By Emma Thompson/Apr 12, 2025

By Michael Brown/Apr 12, 2025

By Lily Simpson/Apr 12, 2025

By John Smith/Apr 12, 2025

By Lily Simpson/Apr 12, 2025

By Rebecca Stewart/Apr 12, 2025

By Emily Johnson/Apr 12, 2025

By Natalie Campbell/Apr 12, 2025

By Jessica Lee/Apr 12, 2025